News

By Timo Dziggel

From October 24 to 26 health experts from around the globe gathered in Berlin for this year’s World Health Summit. Approximately 6000 participants – both virtually and on-site – discussed current trends and challenges in global health. Obviously, the main theme was the ongoing pandemic health crisis. While there was a lot of talk in a lessons learned fashion, the pandemic is far from over. As many attendants including WHO Director-General Tedros underscored, the number one global health priority remains to vaccinate the world.

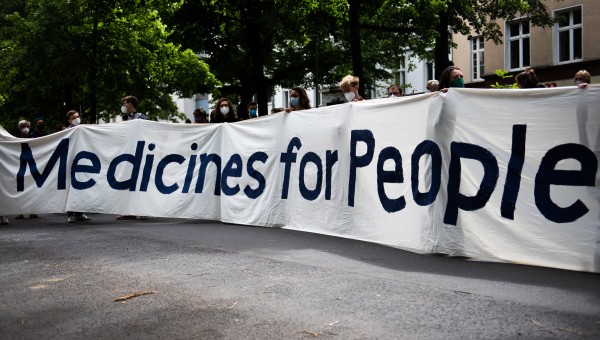

Vaccine inequity thus was one of the more prominently featured subjects. However, the question of a patent waiver was hardly even touched upon let alone discussed. In this regard the World Health Summit constitutes a missed opportunity to push for changes in intellectual property regimes and a TRIPS waiver. For those who participated in the opening ceremony of the summit, this came as no surprise. Whereas civil society was restricted to the listener’s position, two speaker slots were given to Big Pharma representatives alone. This power and representation imbalance was present throughout the event. This was not accidental since the Summit is funded by a third (around €2 Mio) from private sector donations. Surprisingly however, the expression of support for a TRIPS waiver made it into the Declaration of the M8 Alliance, the academic backbone of the World Health Summit, that somewhat guerilla-style appeared on the seats of the last session’s attendants.

A reoccurring theme in this year’s debates was the issue of trust. Particularly, the loss of trust following the vaccine nationalism exhibited by many countries of the Global North. Many participants were right to point out that only by way of overcoming existing vaccine inequities some of the lost trust can be regained. When it comes to trust and global health there is one aspect that only civil society organizations seem to be getting though. There is a growing tendency to securitize global health. Yet to regard the health of your neighboring country as a potential health threat to you is not exactly what you would call a trust building exercise, would you?

Calls for multilateralism and strengthening of the WHO abounded. Particularly, support for a so-called Pandemic Treaty was nearly unanimously. It was framed even as a potential Bretton Woods moment for global health. Yet the discussed proposals to rethink global health remain unambitious. A real Bretton Woods moment in global health would require not only better pandemic preparedness but seismic shifts in the health system as well as neighboring ones. Following the One Health approach, it would require a radical social-economic transformation. Only with such we can hope to overcome the drivers of our current global health crisis.

Promisingly, the WHO presented their new Council on the Economics of Health for All chaired by the economist Mariana Mazzucato also starring the creator of Doughnut Economics Kate Raworth. Its aim is to provide policy recommendations based on placing wellbeing as the prime goal of the economy. Many of the council’s proposals point into the right direction. In a new briefing paper, it calls for debt relief for low- and middle-income countries as well as a redirection of the IMF’s new special drawing rights into the health systems of the Global South to strengthen Primary Health Care.

Next year’s World Health Summit will be co-hosted by the WHO for the very first time. It upgrades the multilateral organization from its role as a mere participant and provides her the opportunity to take influence on the format, e.g. supporting more civil society participation, particularly from the Global South. At the same time, this new partnership marks another manifestation of the growing trend towards multi-stakeholderism in international governance, setting private sector entities as alleged equal actors among other “stakeholders” at the same table with multilateral institutions like the WHO. While this approach totally ignores diverging interests, power and levels of democratic accountability, it offers the private sector improved access to policymaking spaces.

Image: Chris Grodotzki/ jibcollective